17 Jan To Prepare Students With Autism for the Working World, Drones Might Be a Good Start

How do you get students on the autism spectrum interested in STEM careers? And how do you help them feel comfortable in a tech-oriented workplace?

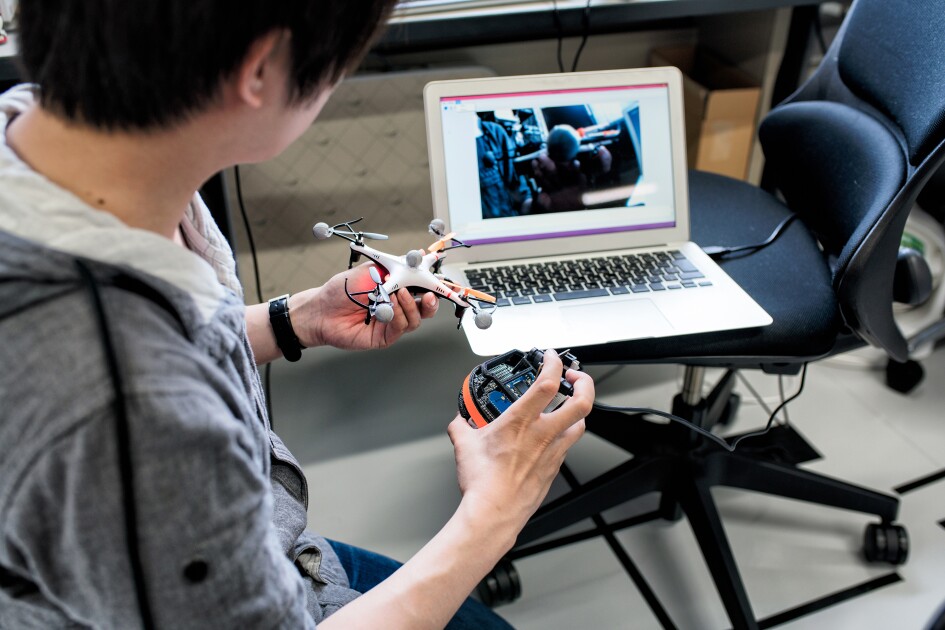

One approach, a group of researchers is finding, is to teach them to fly drones. And specifically, give them opportunities to learn this skill in a classroom environment that simulates a more free-wheeling workplace that embraces neurodiverse people.

Drones are expected to transform everything from retail shopping to the way government responds to natural disasters. And learning how to pilot drones is a useful skill for all kinds of jobs already. Tack on to that the fact that learning to fly drones can be very fun and intellectually rewarding for kids.

That is why a group of North Carolina State University researchers chose drones to be a key part of a study examining how to get students with autism interested in STEM learning and careers. The researchers are currently working with 34 high school students on the autism spectrum. Preliminary findings from the three-year, longitudinal study are scheduled to be presented June 26 at the International Society for Technology in Education’s annual conference in Philadelphia.

According to a 2018 report from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1 of every 60 8-year-olds are diagnosed with autism. Older students on the autism spectrum may have difficulty with social communication, prefer unvarying routines, have trouble expressing emotions, and have a narrow interest in specific topics, according to Autism Speaks, a nonprofit organization.

Learning to fly drones and self-regulate

For the past two years, two cohorts of about 17 high schoolers each have met for six hours over several Saturdays to learn how drones work, through a mix of small group instruction and hands-on learning with a drone simulator. They also get an hour of additional online learning each week, as well as attending a week-long summer session. Students in the program eventually get the opportunity to fly small drones.

As students master the ins-and-outs of the technology, they are also learning how to self-regulate in a simulated STEM work environment, said Jamie Pearson, an assistant professor of special education at North Carolina State who is working on the study.

That might look different for each student, but that is the point. If the students begin to learn what works for them to self-regulate, they will be more likely to learn the concepts of flying drones. For instance, one girl feels most comfortable sitting on the floor of the classroom, even during class discussions.

“She likes the feel of the cold, hard floor. That’s just a sensory input that feels good to her,” Pearson said. “So, you will often see her sitting on the floor under her chair or under her desk, but she is fully engaged. She raises her hand to speak. She answers questions. She follows up on what they talked about the week before. She’s ready to give examples or do hands-on demonstrations.”

At many schools—or later, in the workplace—that kind of behavior would be considered “challenging,” Pearson said. But in the drone classroom, “as long as you’re demonstrating your learning, I really don’t care where you’re sitting, as long as you’re not distracting someone else.”

Some students have tried setting an alarm to remind them when it’s time to shift to a new activity or walking out of the classroom when they need a quick break. Others have benefitted from written reminders of exercises that can help them stay calm, like squeezing a sensory toy.

“We are trying to teach strategies that would actually translate into the workplace,” Pearson said.

Many tech companies in the Silicon Valley have created and encouraged more free-wheeling workplaces, equipped with bean bag chairs, ping pong tables, and other amenities to help workers find the comfort zones that fuel their creativity and productivity.

The study, which was financed by the National Science Foundation, includes students all along the autism spectrum, except those with significant cognitive delays, Pearson said.

“I wanted to make sure that we developed a program that was flexible enough that we could make adaptations for students who had differing support needs,” Pearson explained.

She also made sure that the students represented a variety of racial groups and that girls—who are less likely to be identified as being on the autism spectrum and less likely to pursue STEM careers—were part of the mix.

No Comments